Researchers from a joint Skoltech and University of Sharjah laboratory and their collaborators from Paris Saclay University, France, have identified biomolecules whose levels in nerve tissue are affected in a condition when an infant’s brain gets oxygen-starved during or before birth. This advances the current understanding of the condition that often leads to debilitating permanent disorders, bringing hope for future pharmacological interventions. Funded by a Russian Science Foundation grant and published in Fluids and Barriers of the CNS, the study also introduces a useful model for biomedical research into the brain.

A sharp drop in maternal blood pressure or other factors may interfere with the blood flow to an infant’s brain during or sometimes before birth. Colloquially known as birth asphyxia, this inadequate oxygen supply may result in neonatal encephalopathy — damage to the newborn’s brain. The latter occurs in 0.15%-2.65% of live births (depending on country), often leading to neurodevelopmental disabilities, such as cerebral palsy, which place a lifelong burden on both parents and society. The only available treatment is hypothermic neural rescue therapy, which involves mildly cooling the whole body of the newborn for three days after birth which ultimately reduces brain damage and disability.

Assistant Professor Maxim Sharaev, study co-author and co-director of the joint BIMAI-Lab at the AI Center of Skoltech, said: “The aim is to discover a drug molecule that could be administered once neonatal encephalopathy has been diagnosed to minimize neural damage by targeting specific harmful effects. To achieve this aim, we need to understand what is going on in a brain that’s been affected: how a lack of oxygen affects the levels of various proteins in the brain and which processes are disturbed at the molecular level. For that we need to know which molecules’ levels are elevated or suppressed in hypoxia compared to a normal brain.”

In order to address the above points, a suitable experiment is required. The results from experiments in mice are not necessarily transferable to humans, and tests on human brain cells do not account for the complexity found in an actual brain, which has structure, and its cells are differentiated into subtypes. This is addressed by the team’s study.

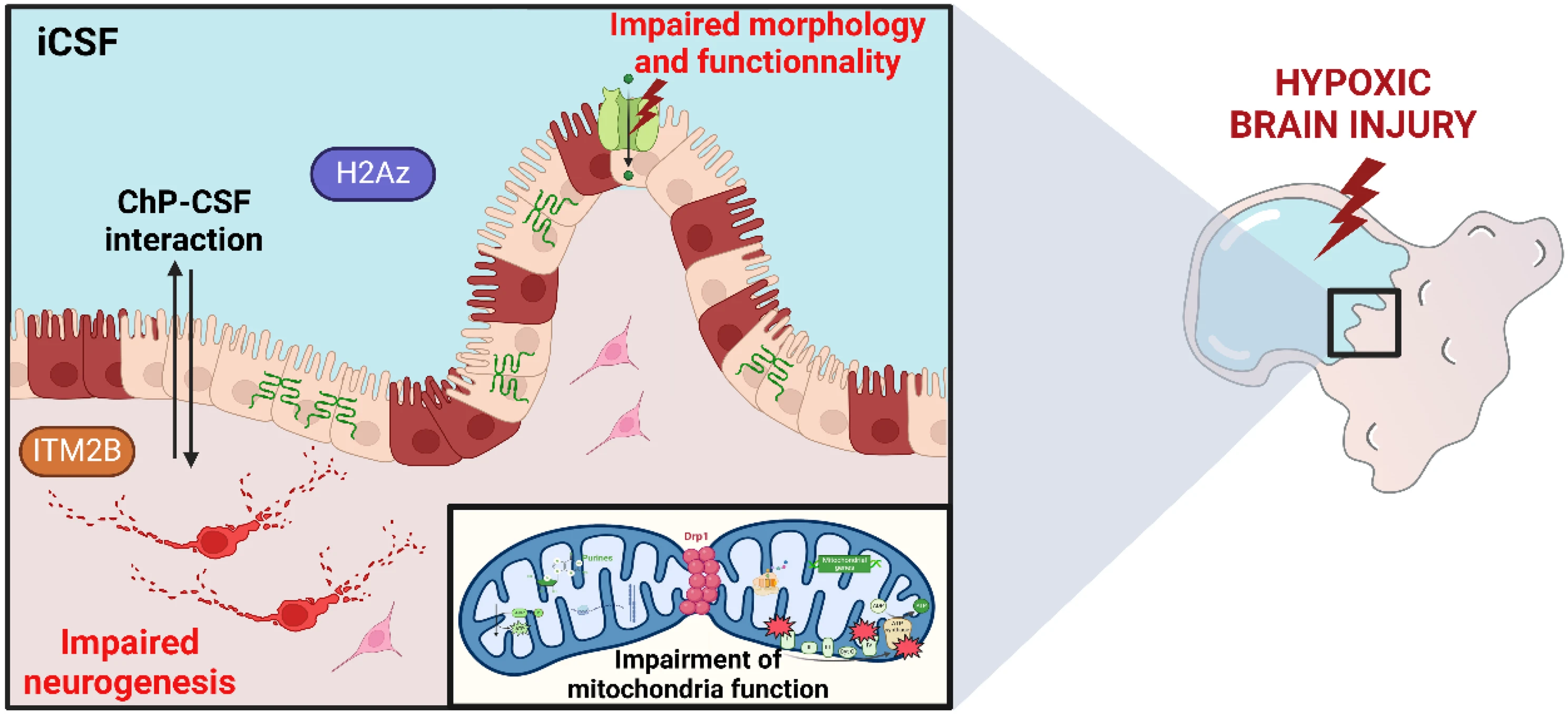

Professor Rifat Hamoudi, study co-author and co-director of the joint BIMAI-Lab at the University of Sharjah, said: “The study generated brain organoids. These are models of various parts of the brain grown from induced pluripotent stem cells, which are obtained by reprogramming ordinary mature cells from various tissues. Some of the organoids were placed in a medium with insufficient oxygen, whilst others were adequately oxygenated. Experimental characterization was carried out to uncover the mechanism of how hypoxia affects the brain’s biochemistry.”